Choosing Open Source Libraries: What you should not do

Enterprises see open source as important, but they also find security to be a main barrier to adopting open source dependencies.

Vulnerable software is, by definition, not secure, but that does not mean we judge security by the number of vulnerabilities. We highlight this by looking at two commonly used libraries, OpenSSL and GStreamer.

Internal software development processes

In RedHat’s recent 2020 version of “The State of Enterprise Open Source” report, 950 interviews with IT leaders worldwide were conducted. From an open source security perspective, there are two very interesting results.

- 95% of the respondents agreed that enterprise open source is important. 75% agreed that it is very or extremely important.

- The main barrier to adopting open source in the enterprise is security.

Security in open source dependencies is of course a main concern since vulnerabilities in these third party libraries are out of control for internal software development processes. Instead, focus and resources must target efficient identification of such vulnerabilities, such that the dependencies can be quickly updated and deployed.

A careful choice of third party libraries can help this process. Open source software with few reported vulnerabilities will not call for updates as frequently. While that might be true, few vulnerabilities do not equal a more secure library. Moreover, few historical vulnerabilities do not mean fewer future vulnerabilities.

Bias in vulnerability

There are many more factors at play here that will affect the number of vulnerabilities. This bias in vulnerability reporting has been highlighted before. As an example, a similar issue in two different libraries could result in several reported vulnerabilities in one, while in the other, only one vulnerability is reported.

The reason why a particular software is even analyzed can have to do with its popularity, current trends, the particular skillset of the researcher, how it is disclosed, etc. Well studied software will on average have more vulnerabilities. To see examples of this, we look at two open source libraries and their distribution of reported vulnerabilities.

OpenSSL

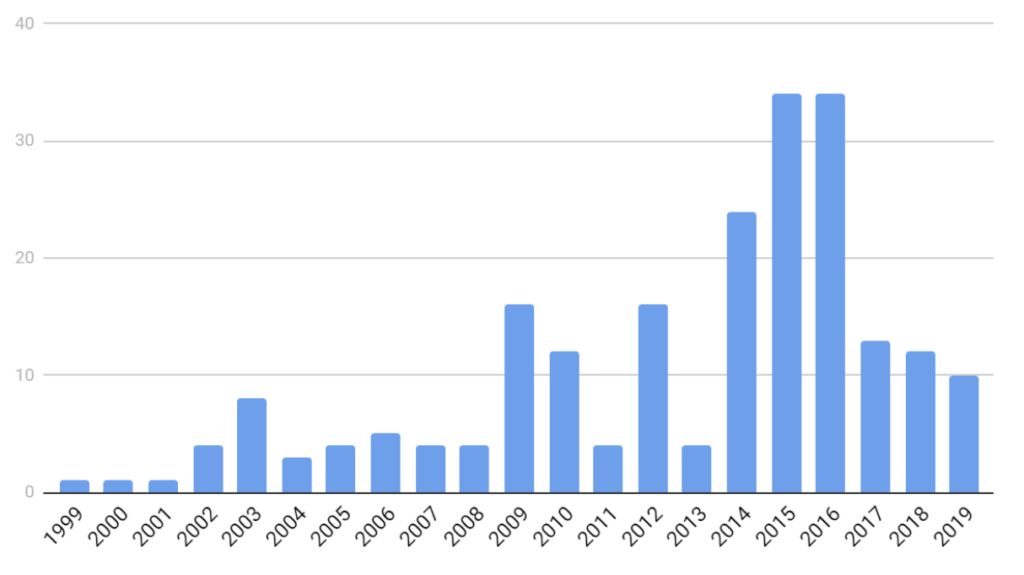

Our first example is OpenSSL, which has had more than 200 vulnerabilities disclosed since 1999. Figure 1 shows the distribution of vulnerabilities since then. We can see that 92 of these were disclosed during 2014-2016, with peaks in 2015 and 2016. A likely reason for this is the disclosure of the Heartbleed vulnerability in 2014. Heartbleed is widely regarded as the most severe vulnerability ever. It affected around half a million TLS-enabled servers around the world, leaking sensitive information.

After the disclosure of Heartbleed, OpenSSL of course attracted the attention of security researchers. This led to the discovery of several new vulnerabilities during the next few years. Does this temporary increase in vulnerabilities during 2014-2016 mean that OpenSSL is less secure than other libraries? Or does it just mean that vulnerabilities that would eventually have been discovered anyway, were discovered (and fixed) sooner? Or can we even say that OpenSSL is (now) more secure than comparable libraries because it has received much attention? In either case, the distribution seems to have been significantly affected by Heartbleed.

GStreamer

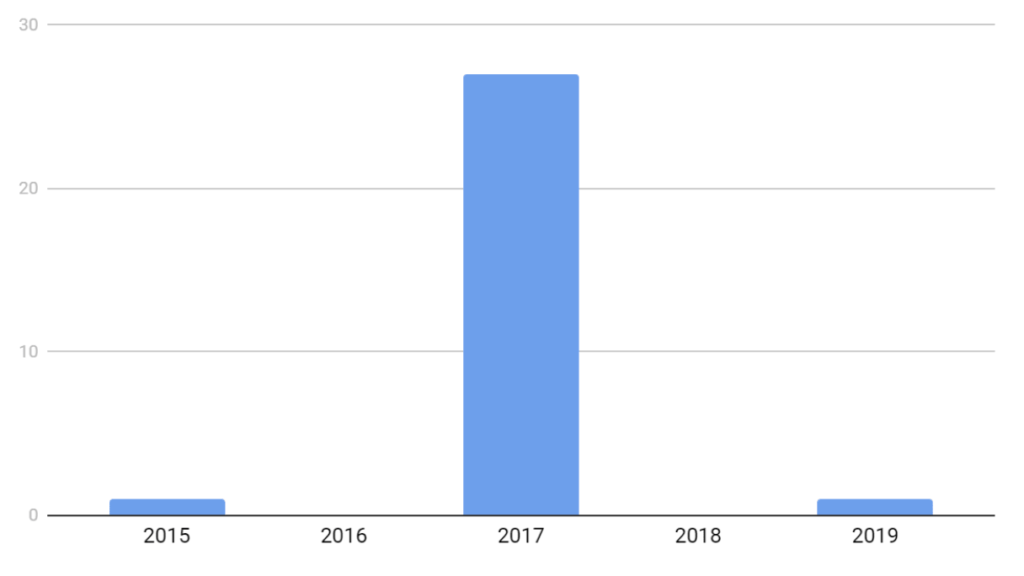

Our other example is the multimedia framework GStreamer. Figure 2 shows the distribution of vulnerabilities. This library has had 29 vulnerabilities, with 27 of them published in 2017. Looking at these 27 more closely we can see that they were all published within a few weeks at the beginning of the year.

This sudden spike started with a blog post, showing a denial of service attack on GStreamer. After that, a few other researchers analyzed the software, discovering several other vulnerabilities within a short period of time. Then it was not until two years later that one more vulnerability was found.

Perhaps the interest in analyzing GStreamer decreased? After all, it was only a few researchers that reported the 27 vulnerabilities. Perhaps many researchers have analyzed it since, but have not been able to find anything? This is of course difficult to answer. What if we would compare it to another, hypothetical, library with one vulnerability in each of 2015, 2017, and 2019? We can not say for sure that GStreamer is less secure because of the spike in 2017. We can not say for sure that it is more secure either.

Conclusion

These two examples show that we can not just define security by looking at the number of vulnerabilities. More important is how the maintainers respond to them. Aspects to consider here is how communication with the researchers is handled and how fast the vulnerabilities are patched.

Still, releasing a new version of the software only solves the problem from the maintainer’s perspective. An even more difficult problem is to get the industry to actually update to the new version. Still today, 6 years after the patching of OpenSSL due to the Heartbleed bug, there are still vulnerable public servers on the internet.